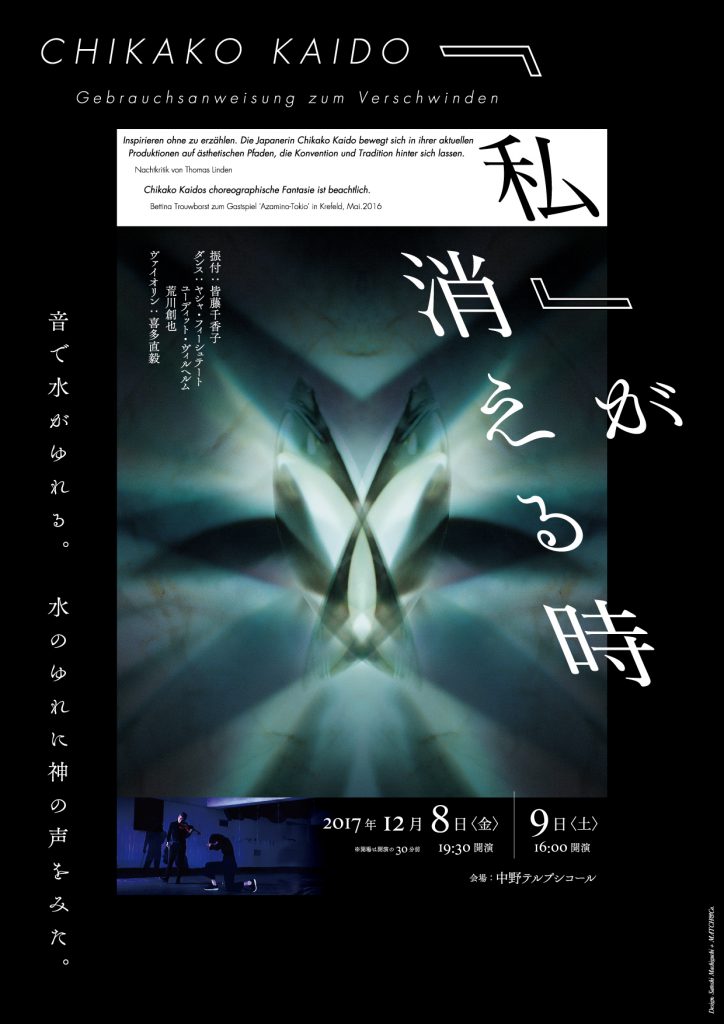

Gebrauchsanweisung zum Verschwinden

2017

PREMIERE Weltkunstzimmer Düsseldof

Theater Terpsichore, Tokyo

Gebrauchsanweisung zum Verschwinden

Nowadays in Japan there is a common spelling: “Be like the air!” The idea of “disappearing” implies a past presence that has left its mark on the present. When we say “disappear”, we know that we are dealing with a victim: the individual. And with an empty space: the memory of his actions. As in a perfect murder, the disappearance can only be observed through the eyes of a witness, in this case the audience. Disappearance can also be seen as an antidote to the dominance of individualism in our society. An alternative to the reality show, to 15-minutes celebrity. Are we prepared to accept the dissolution of the individual, the failure of colours and forms, the fading of the superstar?

This projekt is supported by:

Hans-Peter-Zimmer Stiftung

Kulturamt der Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf

NRW Landesbüro Freie Darstellende Künste e.V.

Kunststiftung NRW

Japan foundation

GEBRAUCHSANWEISUNG ZUM VERSCHWINDEN

Guest performance, Terpsichore Theater, Japan

Tokyo 08.12.2017, Shinichi Takeshige

After seeing the Terpsichore performance in December 2017

Shinichi Takeshige:

This work, as the title suggests, is a question for the contemporary “I” and an attempt to ask whether “dance” still occurs in the body after postmodern dance has taken away the technical privilege of the dancer and made it everyday and anonymous. The aim is very modern. This is because the doubt of “I” (self-identity), which constitutes the foundation of modern democratic society, has been a major theme of modern philosophy since Nietzsche, and in my opinion, Tatsumi Hijikata founded Butoh out of this doubt. The cast consists of four male and female dancers, Jascha Viehstaedt and Judith Wilhelm, along with art performer Soya Arakawa and violinist Naoki Kita, but the movements of the two dancers are deliberately restrained to the mundane, and Kita not only plays but also occasionally takes action with his violin, so there is no hierarchy in the relationship between the four on stage. With the exception of Kita, the three of them, as the title suggests, lack self-consciousness and silently carry out a movement that is indistinguishable from either dance or action. There are scenes where the actors have a relationship with each other, but there is no emotional exchange of any kind. The element of “emotion,” which gives “I” a strong sense of reality, is carefully excluded from the stage, but it is only in Bach’s “Chaconne,” which Kita plays from the latter half of the performance, that it is carried.

However, “When I Disappear” does not consist only of such immediate elements of postmodern dance, but also the fact that the entire composition is interwoven with surrealist dream time is another characteristic of the work. This is especially evident in the image leaps in the second half, when the three perform various tricks with desks and cloaks, and the subsequent theatrical scene in which two men in wooden barrels are pushed by Wilhelm to move around the stage. For the choreographer Chikako Kaido, the unconscious world of dreams is also a way of erasing “I”.

What impressed me the most personally in this performance was the eight-minute solo dance at the beginning of Fishteto, especially the relentlessly repeated rotation. Unlike the pirouettes in ballet, the rotation is unique in that the left foot, which is the axis of the movement, is not left off the floor and the long body is bent slightly, sometimes swaying and sinking, and then spinning to the left. It seemed to be a continual shift between maintaining the balance (the axis that physically supports “me”) and going out of it. There was definitely a dance in which “I” disappeared and its boundaries were exposed, and I think that rotation became a light motif for the whole stage. The fact that we were able to present a light motif that was deeply connected to this theme made this play compelling. Overall, however, the author’s insistence on a postmodern dance-like act that denied emotion seemed unsatisfactory to me. It is true that emotions create the illusion of “I”, but in order to get out of it, it is necessary not to deny the emotions, but to freeze them once and then thaw them out and remake them into something else. After all, it is not an act, but a work of “dance”.